During the SFUSD school closure, we’re offering free weekday admission to youth and families. Learn more…

All Articles

With sumptuous textiles, detailed lacquerwork and forged steel components, a suit of samurai armor is an extraordinarily complex construction of craftsmanship and beauty.

Japanese armor conservation process.

The Asian Art Museum is fortunate in possessing several pre-Meiji period suits of samurai armor. These elegant costumes were intended to celebrate aesthetic ideals in addition to military might. The assembled parts, traditionally displayed upon a wood stand, together create a stunning visual impact that appeals to museum visitors of all ages. Despite the underlying steel, some parts of a suit of armor are surprisingly fragile. Silk and wool lacing, ornamental tassels, and silver brocades are easily damaged by light. To best protect these organic materials from fading and deterioration, armor components are rotated into the galleries for a few months at a time. The other suits ”rest” in dark storage until the next turn comes around. In the spring of 2011, the installation of a set of gusoku-type armor (B83M12) offered an opportunity for thorough conservation, research, and preventive care. Each component of the armor was examined, materials were identified, and conservation treatments performed to stabilize the artifacts for the proposed display. Finally, a custom mount was constructed, and the newly conserved armor installed under controlled lighting conditions in the Japanese art galleries on the second floor.

Japanese samurai armor is typically made up of many small parts and a wide variety of materials. Steel, leather, and wood typically form the protective plating, which may be composed of many small sections laced together using leather or silk cord. Lacquer is then applied over the parts to hide the construction beneath a smooth, glossy surface. The leg and arm guards might be made from chain link or plating, stitched to richly decorated silks and leathers. The addition of finely wrought details such as monograms, fasteners, and ornaments, often in gold and contrasting colors, makes the entire costume a luxurious fashion statement as well as effective protection.

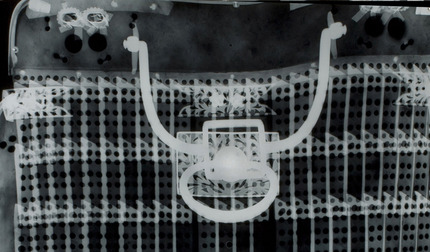

This X-ray image reveals the hundreds of small metal plates making up the do, or body section. The plates are laced together in an overlapping pattern provide strength with flexible movement to the wearer.

Proper display of these costumes can be difficult because materials such as silk, steel, and lacquer have very different chemical structures and respond to the environment very differently. After several centuries, once-strong silk lacings may no longer be able to support the weight of heavy steel plates. Lacquered parts may be bowed, cracked, or flaking, and steel elements may have rusted. Each material needs special attention and any treatment must take into consideration all the surrounding materials as well as the overall function and appearance of the armor. A conservation treatment always starts with careful examination, materials identification, and documentation before any alterations are proposed. Because every case is unique, the pictured steps are chosen to illustrate interesting examples rather than a step-by-step treatment. This is not intended as a teaching tool or a how-to instruction. Armor is delicate and easily damaged — home treatment is not recommended. Always consult a professional for advice on care of your precious art and artifacts.

Whenever possible, conservators choose reversible, age-tested materials that will complement and work with the originals. Below, printed leather bands on the haidate (thigh guards) are repaired to prevent further damage. Small pieces of long-fibered, hand-made Japanese paper are inserted as a fill and set down with a flexible, inert adhesive. The toned paper is flexible and strong, so it can move with the armor without adding bulk.

To support the armor, a traditional Japanese mount was adapted by adding a custom-built internal form. The form was constructed in the Conservation department from layers of starched buckram, foam, and fabric. All of the materials are carefully tested before use to ensure that they will age safely and harmlessly — with care this new mount will provide support and protection to the armor for many years to come.

A traditional Japanese armor mount is a set of tiered wood hangers. The conservation goal was to add additional support for the armor, without altering this minimalist aesthetic.

Once the conservation treatment is completed, the assembled armor appears to be hanging freely on a Japanese-style mount. But beneath the simple appearance lies a great deal of hard work. As with many conservation treatments, the hand of the conservator is intentionally hidden from view. The ultimate goal of a conservation treatment is to preserve the work without distracting the viewer from the intrinsic beauty of these powerful and elegant works of art.

It takes many hands and many specialists to coordinate the installation of such complex objects as this Japanese armor. Textile conservator Denise Migdail, objects conservator Mark Fenn, graduate intern in objects Elizabeth Saetta, intern Jena Hirschbein, and paintings conservator Shiho Sasaki all participated, under the supervision of head of conservation Katie Holbrow. Associate curator of Japanese art Melissa Rinne, mountmaker Vincent Avalos, photographer Kaz Tsuruta, lead preparator Stephen Penkowsky and preparators Patrick Crotty and Evan Kierstad also contributed to the success of this new installation. Find more images of the mounting, photography, and installation of Japanese armor on the museum’s Flickr site. For further details on identification of the armor materials, view the Technical Report.