Think of this amazing material — made from hardened tree sap — as one of the earliest “plastics” used by humans. Artifacts made with this durable polymer have been found in 3,000-year-old Chinese tombs.

Examples of lacquer in the Asian Art Museum’s collection

Lacquer is as tough as a modern, made-in-the-laboratory synthetic, yet comes from a tree. Its unique properties have caused it to be used for millennia throughout Asia for decorating and protecting furniture, vessels, paintings, and sculpture. The result, which may take years to produce, is a beautiful, durable work of art that can last for centuries.

The Asian Art Museum houses one of the most significant collections of Asian lacquer work in the country, including vessels dating from the Warring States period in China (3rd century BCE), virtuoso Japanese tablewares, and Burmese incense containers. The care and study of these precious works has revealed a mine of information about lacquer chemistry, construction methods, sources, and decorative styles.

Nature’s Plastic

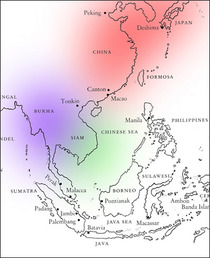

Raw, liquid lacquer is extracted from trees from the sumac-cashew family (anacardiaceae) found throughout East and Southeast Asia. The best known is urushi, grown in Japan, China, and Korea. Urushi is collected by cutting the bark of the tree and scraping off the liquid as it oozes out. Afterward, it is subjected to a range of recipes and painstaking application techniques.

A System of Layers

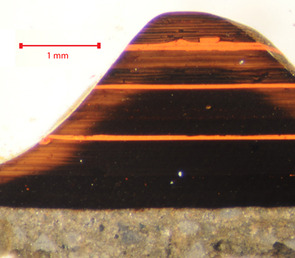

Raw sap from the Anacardium family of trees has a special property: under warm, humid conditions, it will harden into a tough, transparent layer as hard as any varnish. But because each layer must be applied very thinly, it takes multiple layers to build up a thick coating.

1,001 Methods

Lacquer starts out very sticky when fresh and is frequently used as an adhesive. It can glue parts together or be used to adhere sparkling gold flakes, iridescent shell, or mirrors into the design. Adding lacquer to oil, glue, clay, or colored powders can make a putty, so shaping and carving are also options. The slide show below shows a series of objects from the museum collection in which artists have used lacquer’s special properties to create stunning artworks.

Beneath the Surface

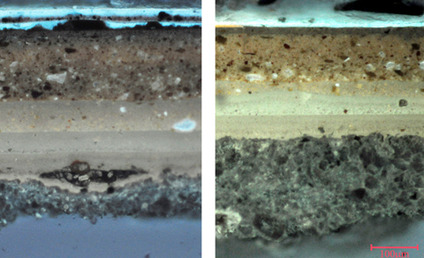

What can we learn from these beautiful objects? Like all art works, the techniques and decorative styles have evolved over time. Even very traditional forms, such as carved red Chinese boxes, may have subtle differences in decoration and construction. Close examination with a microscope or special light sensors may help curators and conservators determine special characteristics that tell us about an object’s use, past life, or current condition.

Treatment

Lacquer is super strong, but like all superheroes it is vulnerable to a few evil agents. Light damage is Enemy #1, quickly causing lacquer to become faded and lose its gloss. Another common problem is seen when the lacquer coating remains strong, but the supporting structure below (often wood) is lost or damaged. Wood furniture, for example, will expand and contract, causing the lacquer coating to crack or give way.

In the conservation studio, a number of steps may be taken to stabilize lifting lacquer. Identifying the problem is always first: is the surface damaged from light, or does the problem lie deeper? What other materials are present beneath the lacquer? How much lacquer is there, and what other components might it contain? Only after these questions are answered does a conservator decide on a treatment plan; because each object may be different, the solution must be adjusted for each treatment.

East and West: Different Conservation Approaches

In Asia, lacquer has traditionally been repaired by adding fresh lacquer as a coating over damaged surfaces or as an adhesive to secure lifting flakes. The advantage of this method is that the materials are compatible and age well together. But in the United States, conservators often prefer to use a modern, reversible acrylic so that the original historic material is easy to distinguish from later repairs. The differing approaches can best be summed up as “compatibility versus reversibility.” Both philosophies have advantages and disadvantages, and recent collaborative scientific studies have demonstrated that different circumstances may call for one or the other, or for a combination of both methods (Rivers et al., 217).

Research Continues

The Asian Art Museum has been at the forefront of this effort to bridge the conservation cultures of Asia and the West. At a symposium held at the museum in 1999, noted lacquer experts were invited to share insights and expertise in the different ways to repair and stabilize damaged lacquer. The resulting book, edited by Jane Williams, is now available as a free download:

Conservation of Asian Lacquer, edited by Jane Williams (pdf)

As science advances, new techniques and instrumentation allow conservation scientists to explore lacquer science on deeper levels. Scientists have used advanced data evaluation in conjunction with pyrolysis-gas chromatography mass spectrometry (Py-GCMS) to identify sap from different species of trees, as well as other components in the lacquer recipes used over thousands of years. Cross-sections of lacquer, examined under a microscope, can tell even more about the structure and composition of a work.

Surprises

The results of this new research technique have been groundbreaking. Aromatic resins, oils such as tung and perilla, glue, and even traces of fruit may be found in the recipe in certain places and time periods. More significantly still, lacquer from the tree species of Vietnam, Thailand, and Burma has been found in Chinese and Japanese objects and European export goods, uncovering new information about Asian trade and technical standards never before considered (Heginbotham and Schilling, 2009).

Rivers, Shayne, Rupert Faulkner, and Boris Pretzel, editors. “East Asian Lacquer: Material Culture, Science and Conservation.” London: Archetype Publications in association with the Victoria & Albert Museum, 2011.

Williams, Jane, editor. “The conservation of Asian lacquer: case studies at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.” (pdf) San Francisco: Asian Art Museum of San Francisco — Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture, 2008.